Another Firestone? Cooper tire workers testify about unsafe production.

August 25, 2000

By Michael Haddigan

The tread came flying off this tire as the Hervey family drove at 70 miles an hour down I-40 to a deadly crash, the plaintiffs’ attorneys say. The same problem sparked the massive Bridgestone / Firestone tire recall.

Three former employees from Cooper Tire and Rubber Co.’s Texarkana and Tupelo, Miss., plants have testified in an Arkansas negligence suit that the company used sloppy manufacturing procedures and cut corners on safety to maintain production.

Chicken bones, soda cans, gloves, sandwiches, plastic – and in one case, a shotgun shell – were among the objects mistakenly baked into tires during manufacturing, workers said.

“I’ve seen everything from a watch cured into a tire, to a time card, to a soda can, to you name it. Aluminum foil – I’ve seen chicken bones,” said Martin Mahan of Texarkana, a 24-year employee.

Asked if any tires with embedded foreign objects made it past inspectors and into stores, Mahan said, “I would be willing to bet my life on it.”

Employees routinely used a repair method requiring them to puncture air bubbles in tires with an icepick-like tool and used a solvent that, if applied improperly, could eventually cause tires to fall apart, the workers said.

Cooper workers, chatting on coffee breaks, sometimes worried shoddy manufacturing practices would one day cause a fatal highway accident.

“Everyone would say, ‘This company is in for some big trouble one of these days if we don’t change our practices,’ ” said William Douglas Eaton of Okolona, Miss., who worked at the Tupelo plant for 13 years.

Eaton and the other workers testified in depositions for a federal lawsuit filed last December by families of four people killed and two severely injured in a 1998 wreck on Interstate 40 near Brinkley.

The families contend a defective Trendsetter II tire made at the Cooper Tupelo, Miss., plant caused the wreck.

The trial, scheduled for next month in Helena before U.S. District Judge George Howard Jr., will convene against the backdrop of a nationwide recall of millions of Bridgestone/Firestone tires.

The recall came after a federal investigation turned up scores of highway deaths linked to a sudden separation of tire tread from the bodies of Bridgestone/Firestone tires. There have been suggestions that many of the faults are linked to production problems at a single Firestone plant, in Illinois.

Plaintiffs in the Cooper Tire case in Arkansas also contend tread separation caused the crash that killed Scharlotte A. Hervey, 37, her husband Edward and son, Onterio Jamar Miller Hervey, 15, all of Little Rock, and Lane A. Whitaker, 23, of Cabot.

Two other sons of the Herveys, Demario, then 13, and Rashand, then 7, were left paralyzed from the waist down.

Attorneys for the Hervey and Whitaker families allege that the tread of a defective Cooper tire on the Herveys’ car separated from the tire body, causing the car to skid out of control across the grass median and collide with Whitaker’s car.

Cooper used a faulty design to build the tire at the Tupelo plant in 1992, and a puncture from an awl allowed water inside the tire that caused the tread to come undone, the plaintiffs say.

Adding an internal nylon band costing less than $1 could have allowed Scharlotte Hervey to maintain control of the car long enough to pull over, attorneys for the families say.

Cooper spokesman Patricia Brown first declined comment on the case, saying the company did not talk about pending litigation. But later she responded with a prepared statement, saying Cooper “properly designed, manufactured, tested and inspected the Herveys’ tire.”

Internal nylon bands, she said, “will not prevent an underinflated or damaged tire from failing.”

Brown said the Herveys’ tire failure was the result of a road hazard. “The Herveys’ tire experienced a tread separation because of an unrepaired punture completely through the tire by a nail or similar road hazard incurred earlier in the tire’s service life,” she said.

The plaintiffs’ attorneys will not say how much they seek in the case.

Last year, Panola County, Miss., jurors awarded $3.4 million to the family of Laura Tuckier, 33, who died in a wreck on Interstate 55 near Sardis, Miss.

Lawyers in that case argued three of the four tires on Tuckier’s vehicle were defective. The tires were made at Cooper’s Texarkana plant.

Based in Findlay, O., Cooper reported $2.2 billion in net sales in 1999, with $1.5 billion of that coming from tire sales. Cooper employs 23,000 workers in 13 countries.

In addition to the Texarkana and Tupelo plants, Cooper operates tire plants at Findlay, O., and Albany, Ga.

CEO Thomas A. Dattilo announced recently the company was increasing production of sport utility vehicle and light truck tires to meet increased demand following the start of the Bridgestone/Firestone recall.

Court documents from the Arkansas and Mississippi cases reviewed by the Arkansas Times yielded a rare and revealing view of the tire factory floor when the Herveys’ tire was made in 1992.

Cooper lawyers attacked the work records of each of the former employees. And they forced each witness to admit they took advantage of employee discounts to drive on the same Cooper tires they criticized in testimony as possibly unsafe.

One former employee, Martin Mahan, however, countered that all available commercial tires are made the same way.

“I think they’re all the same. It wouldn’t matter if it’s Goodyear, Cooper, Firestone, whatever, they’re all made the same,” he said.

Tire builders assemble the first stage of the tire from components in stock, including the sidewalls, polyester ply and inner liner – the “inner tube” of the tubeless tire.

In the second stage, another polyester ply is added, along with two steel belts and the tread. The tire in its raw form is known as a “green tire.”

Curing or vulcanization comes next. The green tire is baked in steam at 355 degrees for up to 15 minutes, depending on the tire’s size. The tire is then inflated for up to 21 minutes to cool and help shape it.

It travels by conveyor belt to final finishing where workers trim excess rubber, buff the veneer, give it a simulated road test, balance and inspect it.

When tires complete the final finishing, they go down chutes into the warehouse for storage.

Bad stock

Among the witnesses in the Tuckier trial was Jimmy Oats of Texarkana, who worked at Cooper’s Texarkana plant for 30 years.

Oats, who left Cooper in 1995, said he personally witnessed tires being made from outdated rubber components, known as “bad stock,” and complained about it.

“Did management take a position on whether to continue to make bad tires with bad stock?” a plaintiff’s attorney asked Oats on the witness stand.

“Yes, sir,” Oats said. “They’d tell you to build them and get them out.”

Oats also said stock would dry out from being stored for too long. Dry stock would not hold together properly and “won’t cure out like it should,” possibly leading to tire failure on the road.

Managers told workers to use up the bad stock, hoping some of the tires they made from it would hold together.

“Some of them did, and some of them didn’t,” Oats said.

Trial transcripts show another former Texarkana worker, Richard Angell, also testified he saw bad stock used to make tires at the plant.

In his deposition for the Arkansas case against Cooper, William Douglas Eaton testified that Cooper workers usually applied a solvent known as “12101” to the dried-out stock to dissolve part of the rubber surface and restore its stickiness.

He was concerned that improper application of the solvent could later cause the tire to come apart on the road.

Eaton, who went to work at Cooper after his retirement from the Marine Corps, said he worried about “some family getting killed out here on the highways.”

The Tupelo plant had roof leaks over the area where the first-stage tire assembly took place, Eaton said. Workers put a plastic sheet over the work area to protect the sticky first- stage tires, but they still got wet.

He was concerned that moisture could threaten the integrity of the tires, he said. But tire builders didn’t want to stop making tires because it would affect their production bonuses, Eaton said.

Mahan testified that water inside the tire will eventually cause the belts to rust and lead to tread separations.

Foreign objects often found their way into the bodies of tires and were sealed in during curing, the workers said. Various tests and inspections caught most of the objects, but small bolts, wood and pieces of plastic sometimes passed through the production line unnoticed, Kirby said.

On one occasion, Mahan said, a worker tried to heat up his lunch wrapped in aluminum foil by placing it on a hot tire press.

Another employee turned on the press and “loaded the tires right onto the guy’s lunch,” Mahan said.

Blisters

Humidity changes often caused air bubbles, known as “blisters,” to become trapped between the inner liner and the outer layers of the tires.

Cooper officials instructed workers that up to eight thumbnail-sized blisters could be repaired on a tire by piercing them with an awl issued by the company, workers said.

Eaton said he saw tires with blisters repaired using an awl.

He explained how it was done:

“They would locate the blister inside the tire with their hands, and then they would take an awl, and they would insert the awl through the tread, the two belts, and the ply, feeling with their finger until they penetrated down to the blister without going through the liner,” he said. “And the air would escape, and they would retract the awl, smooth it over with their fingers, and let it go.”

Management was surely aware that it was done because he once saw a quality control manager demonstrate the repair method to a worker.

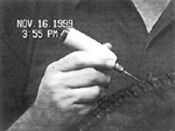

A former Cooper tire worker demonstrates on videotape how workers punctured tires with an awl to fix air bubbles. Families of crash victims contend this repair method helped cause the failure of the Herveys’ tire.

Mahan demonstrated the repair method during his videotaped deposition in the Arkansas case.

Mahan said he feared the practice might cause damage to the tires’ inner liners. He complained to his boss about it, but the company did nothing, he said.

“I told my boss this was going to bite us in the ass,” he said.

He said such repairs were made to as many as eight hundred tires a day, but on some days workers lost count.

The Tupelo plant produced up to 32,000 tires a day, he said.

Cooper spokesman Brown denied the company used any substandard material in its tires. She also said solvents such as “12101” and awls “may be properly used in the manufacturing process; however, focusing on the Hervey tire, there is no evidence that any solvent or any awl was used on this tire.”

Repaired tires were supposed to be marked as such but rarely were, Mahan said, and the tires were sold as high quality tires, not seconds.

Tires that failed inspection were scrapped, but the company’s bonus system encouraged workers to keep the scrap rate low.

“If your scrap rate was low, your overtime was low, your expenses were lower, the more bonus you got,” Mahan said. “Some people made more money on their bonus checks than they did on their regular paychecks.”

Under questioning by a Cooper lawyer, Mahan acknowledged that badly made products make it into the market in any industry. But he turned the question back on the lawyer.

“Unfortunately, we’re in an industry that if scrap gets out it kills somebody,” he said.

Mahan said the “pressure was always on” to produce more tires.

“Management, I felt, sometimes passed some things that shouldn’t have been let go,” he said, “for the almighty dollar, the bonus.”

Despite his concerns about some of the manufacturing faults, Mahan said he was a loyal employee at the Texarkana and Tupelo plants. He rose from laborer to foreman and performed most of the jobs in between.

“Cut my arm, I would be bleeding Cooper Tire blue. I’d do anything they asked me to.”

But Cooper’s regard for employees sometimes shocked him, he said.

In 1992, a manager told Mahan, “I love tire builders. You just use them up and throw them away”

Mahan said he was stunned.

“I can’t believe you just said that,” Mahan replied. “Man, these are people.”

The manager then said: “No, man they’re just bodies. They’re not people. Just use them up and throw them away.”

A Cooper lawyer asked if the manager’s comment was official company policy.

“This man had 520 tire builders working for him, that was his policy,” Mahan replied.

Inspections

Mahan, Eaton and Kirby each testified about questionable or faked quality control checks at Cooper. The worst appear to have been at the expense of the Atlas tire company.

Atlas was one of more than 50 brands manufactured at the Cooper plants, Mahan said.

Some companies sent representatives to tour the plant and play golf. “It was a dog and pony show,” he said.

But Atlas was the only company that carried out inspections.

Cooper officials carefully prepared tires for inspection and then rigged inspections to ensure the tires would pass the audit.

“I personally have shown the man the same tire thirty times,” Mahan said.

Kirby gave a similar account, saying Cooper officials spent weeks specially producing near perfect specimens of stock to show Atlas inspectors. And Kirby said he was also aware that flim-flammed Atlas inspectors examined the same tires repeatedly.

“I’ve seen it happen time and time again,” he said.

Cooper’s normal production process included more than a half-dozen quality control checks. But Mahan said the pressure to produce tires often overwhelmed Cooper’s own quality control inspectors.

Even under ordinary circumstances, he said, some employees who inspected finished tires had only 18 seconds, sometimes less, to examine a tire for defects.

Once the company sent Mahan to San Francisco to inspect tires that had been manufactured at Findlay, O., and Tupelo and shipped by rail to the West Coast.

Of the 800 tires he and another man inspected, about 50 had to be discarded for faults like blisters and tread separation. One had a glove cured into the sidewall, Mahan said.

In 1996, Eaton said, he decided to test the Tupelo plant’s quality control procedures.

“I knew that tires were getting in the warehouse that I didn’t think should be there, so I slit the sidewall of a tire,” he testified.

He used a knife to cut a three- to four-inch gash in the side of a scrap tire.

“It went all the way through the plies, liner, everything,” he said

Later, he looked for it among completed tires in the plant’s warehouse.

“I had to go through the warehouse, through the tires over there, to find it. But it went through the complete process and ended up in the warehouse,” he said.

When he first started work at the Tupelo plant, the company put out good tires, and quality control procedures were effective, Eaton said. But quality deteriorated as production demands increased.

“When we first opened that plant up, we had a quality orientated plant, but as time went on and they got started pushing more and more for production, then quality went to the wayside,” Eaton said.

The Tupelo plant produces more than a million tires a year, he said.

In his testimony, Kirby said Cooper officials frequently said the company’s priorities were quality, safety and production.

“Well, in my personal opinion – excuse my language ma’am,” he said with a nod to the court reporter, “it was just ass backwards to that. It was production, safety and quality.”

Tire Defects – Serious Accident and Injury Legal Help

If you or a loved one have been seriously injured, or a loved one has been killed, as the result of a tire defect, tire failure, tread separation, tire blowout, rollover accident, or any other serious injury accident, then please call us to discuss your legal rights to a potential product liability lawsuit. Please fill out our online form or call us right now: Toll Free 1-800-883-9858.